Innovation goes beyond new product development (NPD) and requires a cohesive strategy

Herman Miller, GE, and Godrej & Boyce (India) are three multinational companies that I have worked in over the course of my innovation career. Like many large corporations, they spend hundreds of thousands, if not millions of dollars, into what is known as Corporate Research and Development (R&D) and New Product Development (NPD). Corporate R&D practices, at least the traditional ones, focus on managing technical risks of a new product — focused on a product made with all the knowledge contained in that organization at that time. More often than not, these programs are measured by accumulation of IP (patents, copyrights, and trademarks) with the expectation that it will somehow magically result in cash flow and increased shareholder value.

If you have been reading my previous articles, you will note that it is not enough to build around the creation of new ideas, you must also consider the flow of the idea through the company’s structure. Creating the context in which innovation takes place before ideation and shaping market success after the product development is equally important for innovation success. Traditional R&D approaches are problematic from this perspective because they:

- Focus too much on the product

- Focus on what we can do now versus what the future entails

- Focus on management of technical risk and not market risk

- Work in silos and rely on business units to commercialize the invention

- Use evaluation metrics that are biased towards immediate returns.

R&D and NPD functions should not be confused with innovation — they serve two different roles in an organization’s innovation structure. R&D and NPD should be seen as inputs to the innovation process. Innovation is not invention, it is streamlining the flow of ideas across the organization, of which R&D is just a part.

When R&D and NPD are branded as innovation, it disrupts flow in three ways:

1. Disconnected: NPD efforts and business strategy are seldom connected but they should be

A recent PWC report explains how executives struggle with bridging the gap between innovation strategy and business strategy. 65% of companies which invest over 15% of their revenue in innovation indicate that aligning business strategy with their innovation vision is their top management challenge.

This is a problem we see across the board. Companies have portfolios and portfolios contain products. NPD comes up with a new product and then the search is on to see which portfolio to connect it to. The core of this problem is the fact that NPD focuses on reducing technical risk. Market risk is an afterthought, something that you hand off to someone else in the company. The normal story which you have probably heard is a business executive is shown a new product, gets excited and asks a business unit head to find a way to bring the idea to market. Little to no evaluation is made whether the product fits in with other ideas in the company’s portfolio.

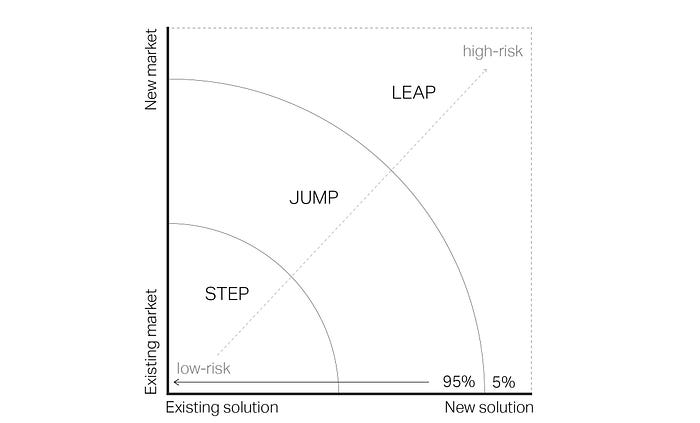

While this problem cannot be fully addressed through innovation, there is a way to think about how products fit into portfolios and how ambiguity can be seen as a resource instead of a risk. Patrick Whitney, the former Dean of the IIT Institute of Design, proposes that companies should look at their products through two lenses — ambiguity and risk appetite. The lower the risk and higher the clarity, the faster and quicker should be the development cycle. He calls these Step and Jump innovation. More ambiguous and higher risk means more exploration and problem definition is required. He calls these Leap innovation. You want to ensure that the organization’s innovation ambition is aligned with the overall company strategy. Based on where the idea falls in the spectrum of risk level the process, skills needed and time required for completion will be completely different.

Companies should have a right mix of initiatives in their innovation portfolio. You cannot have all high ambiguity, high-risk projects. Nor can you have too few of them. Whitney claims that a good innovation portfolio should contain 95% low risk, low ambiguity (Step and Jump) projects and 5% high-risk, high ambiguity (Leap) projects. The key is that the 95% Step and Jump will have a higher rate of success. These, however, lead to limited growth as competition is also working on similar ideas. On the other hand, the 5% Leap projects are highly unlikely to succeed but if they do, it will be a gold mine for the company. Very few of the other competitors will be focused on this type of innovation. At a very minimum, Leap projects expose new opportunity spaces that the company never imagined was within their grasp.

Case Study: When Phil Knight returned as a CEO of Nike in 2006, he knew they had to do something different. At that time Nike made a shift in their mission from “Crush Adidas” to “Bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world”. This was highly risky and ambiguous strategy for a company that had focused on making shoes for much of its life. Leaders had to align this new strategy with their innovation efforts. They reduced their risk by bringing in programmers, technology developers, sensor technologists — people outside of the traditional footwear industry. They reduced their ambiguity by understanding the explicit and implicit needs of their target audience — “athletes”. Net effect: From 2006 to 2016, Nike doubled their revenue (from $14B to 34B).

2. Disbalanced: Corporate R&D cannot replace fast-paced startup innovation but they can learn from it

Traditional R&D processes are expected to bring long-term value but happen in a silo focused on invention. Only after the idea has evolved is when it is shared with other functional groups. This process slows down the chances of actual implementation. Commercialization and customer acquisition starts after the R&D process and is done by different people from the ones who came up with the idea, introducing a significant barrier to the flow.

Compare this to the startup world. Technologists who come up with an idea work hand in hand with the business people who market and commercialize it. Successful startup founders, even ones coming from a technical background, have a vision for actual commercialization. Lean methodologies are incorporated into the startup process because it offers speed and operational efficiency. Large corporations cannot keep up with this type of flow because of how nimble the startup flow is.

Think of it like a pendulum which swings from traditional R&D focused on the invention to startups focused on commercialization of that invention. The truth is there needs to be a balance and synergy between the two approaches to ensure innovation success. When companies cannot maintain a balance in this swing, they go on an acquisition spree — sometimes buying out startups doing the same exact thing as their R&D groups. One is not necessarily better than the other, just different. Companies can learn from startups by adopting similar lean methodologies to promote in-house flows and powerful ideas with the institutional knowledge and long-term values embedded in the organization — things that startup can only dream of.

Case Study: GE consulted with thought-leaders like Eric Ries and others to balance the pendulum using lean startup methodologies to fasten the pace of innovation. FastWorks is a GE program informed by Lean Startup principles, which was developed by GE and Eric Ries, author of the bestselling book The Lean Startup. FastWorks is a mindset that takes aspects of the Lean Startup movement — namely the flexible and transparent characteristics of a startup — and combine them with GE’s size and resources.

3. Discordant: R&D processes hit up against governance barriers but just enough separation can be good

R&D functions are often force fitted into the hierarchical structure of an organization. This happens because it is easier to access funds within existing business structures. Executives can justify R&D and NPD by claiming it provides long-term value to the company and ultimately to shareholders. However, it also means that the same processes used for business success are used to evaluate innovative thinking and ideation. By borrowing from one part of the organization to the other, you set up innovation processes to fail from the get-go. On the other hand, the innovation process requires metrics that reward people who experiment, challenge the status quo to leverage existing corporate as well as R&D knowledge and combine it with other outside-in thinking to come up with new futuristic solutions and business models.

Jean-Philippe Deschamps in his book “Innovation Leaders” suggests that organizations can simplify this into two phases of innovation (which refers to as the i-process):

1. Creative invention phase: Immersion (in the market and the technology), Imagination (of an opportunity), Ideation, Initiation (of a formal project).

2. Disciplined implementation phase: Incubation (of the project), Industrialization, Introduction (in the market and roll out), Integration (of your offering into the customer’s operations).

Successful organizations follow a simple strategy. They differentiate the creative invention phase from the disciplined implementation phase. They carefully divide these two phases and put governance barriers between them so one does not influence the other. The key to innovation success is the seamless transition of the idea as it moves from one part of the process to the next without loss of intent, knowledge, and connectedness to the overall business strategy.

Mapping an innovation flow that goes beyond NPD

When I work with innovation leaders, I stress the importance of understanding flow of innovation and how critical it is to the corporate mission of growth and impact. I suggest that they start the creative invention phase by evaluating and building an innovation flow, formulating a business challenge, and defining a problem statement. Then bring in R&D and NPD as inputs at this point. To ensure the success of ideas, you must ensure that the organization’s innovation ambition is aligned with the overall company strategy early on through ideation, prototyping, journey mapping and user feedback. The best ideas should be prioritized based on desirability, viability, and feasibility of the solution and mapped to the existing portfolio of the company. If it does not fit with the business strategy of a unit, then companies should seriously consider spinning it out of the corporate governance structure.

If relevant, then ideas should be taken into an incubation stage where it is built and tested as part of the disciplined implementation phase. The value proposition of the idea is established and the value narrative is created and tested alongside. A minimum viable offering is piloted with a friendly customer to continuously improve the solution. After sufficient improvements based on the feedback from the users and the stakeholders, the solution is ready to be scaled and commercialized because it is a seamless part of the business unit, not force fitted into it.

The three companies that I mentioned in the beginning — Herman Miller, GE, and Godrej — are constantly experimenting with new models of innovation. They have each tried different ways to solve this problem of innovation flows and in some instances, I was part of the team that did it. The more the companies acquire agencies for design and innovation capabilities the more important innovation governance becomes to them because of needing to change traditional mindsets and removing existing silos. Irrespective of the part you play within the innovation process, whether it is strategy, new business development, design, research, product management, commercial or software engineer you must look out to fix three barriers to innovation — disconnected, disbalanced, and discordant flows.

‘Innovation goes beyond new product development (NPD) and requires a cohesive strategy’ is the second of the five insights to consider if you are responsible for understanding innovation flow at your organization. This is part 3 of a 6 part series that begins with my first insight “Innovation is not ideation”

In the next article, I will elaborate on how too much of the “Just do it” culture and focus on lean startup approach can cause a lot more waste than necessary. Please follow my stories on Medium. If you have comments, please leave them below or email me directly at shilpi.kumar@khojlab.com

A special thanks to people whose comments and advice informed the content in this article: Jim Long (Herman Miller), Patrick Whitney, Anijo Mathew, Tom MacTavish, Matt Mayfield (Institute of Design, IIT Chicago), Farid Talhame (Godrej & Boyce), Jeff Hsu (Far Eastern Group), Mandy Tahvonen, Kate Micheels, Nick Florek (Relish Works), Mike Alexander, Praseed Prasannan, Eric Heller, Nicole Ciminello, and Patrick Smith (GE Transportation Digital).